Compassion across Cubicles

By Jill Suttie“Our department is special,” said Sarah Boik, head of the billing unit. “People care about each other here.”

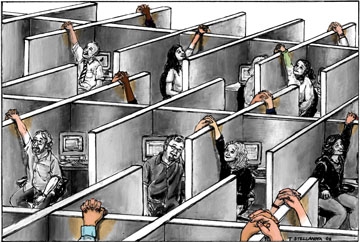

Tammy Stellanova

Deb LeJeune agrees. LeJeune had been on Boik’s staff for only five months when her husband needed a kidney transplant. She said she was worried and distracted in the days leading up to his operation and couldn’t concentrate at work. She needed to take six weeks off without pay to care for her husband, a financial strain she wasn’t sure she could handle. When her co-workers learned of her situation, they pitched in to make her a basket full of puzzles, books, and snacks she could take to the hospital, took up a collection to help her make her house payments, gave her gas cards to use for the drives back and forth from the hospital, and visited her at home just to check in on her.“It was amazing!” said LeJeune. “I couldn’t have gotten through without their support. They are like family to me.”

These days, it’s rare to find people who consider their workplace “special” and feel close to their co-workers, let alone call them “family.” Denise Rousseau, a professor of organizational behavior at Carnegie Mellon University, traces that fact to a steady deterioration in employer/employee relationships that began in the 1980s, when changes in technology, globalization, and a volatile stock market pushed major manufacturers to lay off large numbers of employees. Other organizations followed suit, and soon managers were hiring and firing their workers at will. “The downsizing surge in the ’80s left employees feeling betrayed,” said Rousseau. “Employees no longer felt they could trust their employer to provide for them, so they had less attachment and loyalty toward their places of work.” Rousseau’s statements are borne out by statistics from a recent Gallup poll, which found that 59 percent of American workers are disengaged from work—putting in their time, but with no energy or passion for it—while another 14 percent are actively disengaged, acting out their unhappiness at work and undermining co-workers.

But a growing number of researchers, mainly at business schools across the country, are working to determine what’s behind anomalies like the Foote billing department, where ennui and malaise are displaced by excitement and compassion. This movement, called Positive Organizational Scholarship, or POS, breaks with traditional business research. Instead of analyzing organizational failures, POS looks for examples of “positive deviance”—cases in which organizations successfully cultivate inspiration and productivity among workers—and then tries to figure out what makes these groups tick, so that others might emulate them. “We’re a combination of positive psychology, sociology, and anthropology,” said Jane Dutton, a professor of psychology and business at the University of Michigan, and a leader in the POS movement. “POS seeks to cultivate hope and a sense of possibility that people don’t always know is there.”

Positive Organizational Scholarsip esearchers (clockwise from top left) Monica Worline, Jane Dutton, Jacoba Lilius, and Jason Kanov. Ameen Howrani

Positive Organizational Scholarsip esearchers (clockwise from top left) Monica Worline, Jane Dutton, Jacoba Lilius, and Jason Kanov. Ameen Howrani Dutton sees compassion as a natural response to people witnessing others in pain or distress—something we are hard-wired to do. The problem with bringing compassion into the workplace, she explains, is that people don’t know what’s acceptable to express in that setting. Many workers assume that they are supposed to check their personal problems at the door when they enter the office. “Ever since organizations began moving toward more bureaucracy and measuring success by reliability and efficiency, the relational aspects of work have been de-emphasized,” said Dutton. But when stress at home inevitably spills into the workplace, Dutton added, it can contribute to lost productivity and higher health care costs, and compassion becomes a vital response. “If compassion heals, as our research suggests, then people will be able to get back to work more quickly, to bounce back from life’s setbacks,” she said. “This has to be of interest to employers.”

Thomas Wright, a researcher in the University of Nevada’s managerial sciences department, agrees that managers would do well to pay more attention to the mental health of their employees. In several studies, Wright has found that psychological well-being accounted for 10 to 25 percent of an employee’s job performance, and was predictive of positive employee evaluations up to five years in the future. “Organizations that are able and willing to foster a psychologically well workforce and work environment are at a distinct competitive advantage,” said Wright. “Managers should take note.”

Apparently, some are. At Cisco Systems, a California company that creates technologies for the Internet, whenever an employee suffered a significant loss, such as a death in the family, CEO John Chambers made it a policy to contact that employee within 48 hours to offer his condolences and help. His example gave others within the organization a green light to act compassionately toward their co-workers, and employees consistently rate the company as one of the best places to work in the country. “When an organization’s capacity for compassion comes from the top, it can result in a kind of compassion contagion that sweeps the whole organization,” said Dutton.

In the Michigan hospital department where Sarah Boik (left) and Deb LeJeune work, staff members hang a star with each co-worker's name on it every time someone does something exceptional. Their office has been studied as an example of a compassionate workplace. Roger Varland

In the Michigan hospital department where Sarah Boik (left) and Deb LeJeune work, staff members hang a star with each co-worker's name on it every time someone does something exceptional. Their office has been studied as an example of a compassionate workplace. Roger Varland Still, many organizations have neither a compassionate manager nor an environment that fosters compassion among colleagues. One financial analyst, who works for a large national bank in the San Francisco Bay Area and asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal, spoke in an interview about his office environment, where employees work side-by-side every day but barely acknowledge each other. Having come from a smaller, more familial software company, he was surprised by the lack of camaraderie at the bank. But he soon found himself adjusting to the new environment, keeping his own natural friendliness in check. Then a co-worker on his floor died suddenly over the holidays. “I expected a supervisor or someone to at least explain why he wasn’t there, but nobody talked about it. It was really weird,” he said. “I didn’t learn he’d died until I needed an office space for a new hire, and they suggested I use his.” Given the culture of his office, the incident wasn’t surprising, he said, but it made him question the heart of the organization.

Worline said that such environments take their toll on people working within them. “In extreme cases, employees leave,” she said. “But even those that stay will often quit doing the discretionary things they used to do for the organization, when they thought it cared.”

It isn’t always easy for a boss to accommodate employees, even when one is committed to demonstrating compassion. “All supervisors have to balance the needs of the corporation—which is all about money, earnings per share, and profitability—with the needs of the worker,” said Renee Knee, a senior vice president for SAP, a leading software company. She cited an example of a senior employee who had to leave the country suddenly because of a death in his family, just before the deadline of a multi-million dollar project for which he was responsible. Though Knee gave him the time off, the ill-timed departure created extra stress in an office already under deadline pressure.

Organizations, especially businesses in competitive industries, always walk a fine line when giving employees time off in emergencies. But Worline suggests that the POS message about compassion sometimes gets misconstrued, as managers only focus on the bigger acts of compassion, such as time off and monetary gifts, which may make a big difference to workers but are not always easy to provide. “Just stopping by and listening to an employee in pain can make all the difference,” insists Worline. When giving talks to groups of managers, she tries to convey the importance of just paying attention to employees and noticing when they need help.

Worline, Dutton, and their POS colleagues recognize that problems can arise in practicing compassion at work. They note that compassionate acts must be tailored to the particular needs of each person. If a person suffers a traumatic event and wishes to remain private about it, he or she may not welcome attention or help from others, well-meaning as it might be. Programs like vacation pools, where employees donate small amounts of vacation time for coworkers in need, can create complicated ethical dilemmas: If an employee doesn’t contribute to the vacation pool, should he be allowed to dip into it himself? “Compassion, if applied differently to different employees, may create a perception of inequity,” said Worline. If applied in this spirit, it may even alienate employees, she argues.

Then there are the researchers who take issue with some of the basic objectives of POS. Ben Hunnicutt, a professor of leisure studies at the University of Iowa, argues that efforts to make work life more rewarding and pleasurable distract from what he considers bigger goals for workers, like higher pay and shorter work weeks. Encouraging people to pursue satisfaction through work means that they’ll spend more time there and have less left for family, health, art, religion—the things, he argues, that really give meaning to people’s lives. “Work can never replace these important aspects of life, and we shouldn’t expect it to,” he said. “Instead of trying to make work better, we should all be working less.”

Dutton agrees that working less may help improve people’s lives, but she thinks American society is a long way from moving in that direction. If anything, people are working more than they used to, she said, and economic realities require people to spend more time at work. And she added that her work on compassion is not just relevant to work settings, but to organizational settings in general. The conditions that foster compassion at work apply to other contexts as well. “Whether we’re talking about work, schools, churches, or hospitals, we all spend time in organizations,” said Dutton. “POS is trying to understand how all organizations can be places of healing, where people feel alive and can flourish.”

There are signs that Dutton’s and her colleagues’ ideas are gaining wider recognition, including the publication of POS scholarly work in journals aimed at business managers, and the inclusion of a chapter on compassion in two recent management textbooks. When a POS article appeared in the Harvard Business Review in January of 2005, over 200 individuals from businesses, schools, and hospitals called in to participate in an online conference with the authors, arranged by the magazine. Dutton says none of this would have happened even a few years ago.

“It’s exciting to see how interested people are in our work, how it energizes them,” she said. “They want to move toward more humane interactions at work, more compassionate responding. This is deeply motivating to me and my colleagues.”

0 comments